Of all the future predictions made in Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey, there’s one that the movie got entirely right. It’s not the lunar colonies or zero-gravity stewardesses, but rather the tablet used by astronauts that looks almost identical to today’s iPads. As author Arthur C. Clarke described it in the 1968 novel of the same name, these devices were called “newspads” and could be plugged “into the ship’s information circuit (to) scan the latest reports from Earth. The postage-stamp-size rectangle would expand until it neatly filled the screen. When (an astronaut) had finished, he would flash back to the complete page and select a new subject for detailed examination.” Unfortunately, neither Kubrick nor Clarke lived to see the iPad get released in 2010.

In the early 20th century, home telephones were still a relatively new innovation. So it was audacious for Nikola Tesla, an engineer and inventor who briefly worked with Thomas Edison, to suggest, in 1909, that someday people would be walking around with phones in their pockets. But, as he explained to The New York Times, “It will soon be possible to transmit wireless messages all over the world so simply that any individual can carry and operate his own apparatus.”

Predicting that the United States would someday have an African-American president? Not that impressive. Predicting that the United States would have an African-American president a full 40 years before it happens, and picking his name as “President Obomi?” Well, now you’ve got our attention. Stand on Zanzibar, an award-winning 1969 science fiction novel set in 2010, was just two letters off the real future president’s not-so-common last name. How do you begin to explain that? Author John Brunner also predicted DVRs, satellite news, terror threats, and legal marijuana. But we still can’t get over that “President Obomi” character.

Leave it to a college-dropout-turned-science-fiction-author to come up with the idea for credit cards. The concept was first introduced in Edward Bellamy’s 1888 novel, Looking Backward, and as one character explains it, each person is given a physical punch card “with which he procures at the public storehouses, found in every community, whatever he desires whenever he desires it. This arrangement, you will see, totally obviates the necessity for business transactions of any sort between individuals and consumers.” It’s a utopian vision of the future, though many credit card owners may disagree with that whole “whatever he desires whenever he desires it” part—especially after last month’s bill!

To be fair, a lot of fiction imagined what it might be like if human beings were capable of flying to the moon. But From Earth to the Moon, a 1865 novel by author Jules Verne, got closer with more of the details than most. Sure, the general premise was kind of silly—a giant cannon fired a manned projectile into space—but he wrote about the weightlessness that astronauts experienced, something an author in the mid-19th century would have no way of knowing. Verne also predicted that there would be three astronauts on that first moon mission—though his astronauts never actually walked on the moon—and that Tampa, Florida, would be the launch site. (The Apollo 11 mission launched from the Kennedy Space Center, in nearby Orlando.)

Fourteen years before the ill-fated Titanic hit an iceberg while en route to New York, killing 1,517 people in the icy Atlantic, author Morgan Robertson penned a tragedy-at-sea tale called “Futility, Or The Wreck of the Titan,” in which another supposedly “unsinkable” boat sank after hitting an iceberg. The similarities are truly creepy, right down to the name of the boat—Titan—but as Titanic scholar Paul Heyer explained in an interview, Robertson was far from a prophet. “He was someone who wrote about maritime affairs,” Heyer said. “He was an experienced seaman, and he saw ships as getting very large and the possible danger that one of these behemoths would hit an iceberg.”

The first major organ transplant happened in 1954, but chemist Robert Boyle had already predicted its arrival more than 300 years earlier. Boyle, who was often called “the father of modern chemistry,” created a “wish list” for the future, imagining all of the advances that awaited humanity in the coming years. Almost all of his predictions have come true, including his belief that one day science would be able to cure all diseases “by transplantation.” Sure, we haven’t quite cured “all” diseases just yet, but organ transplants have made some deadly diseases less deadly. The fact that he made this prediction in 1660, when the medical world knew so little about how internal organs actually worked, is kind of incredible.

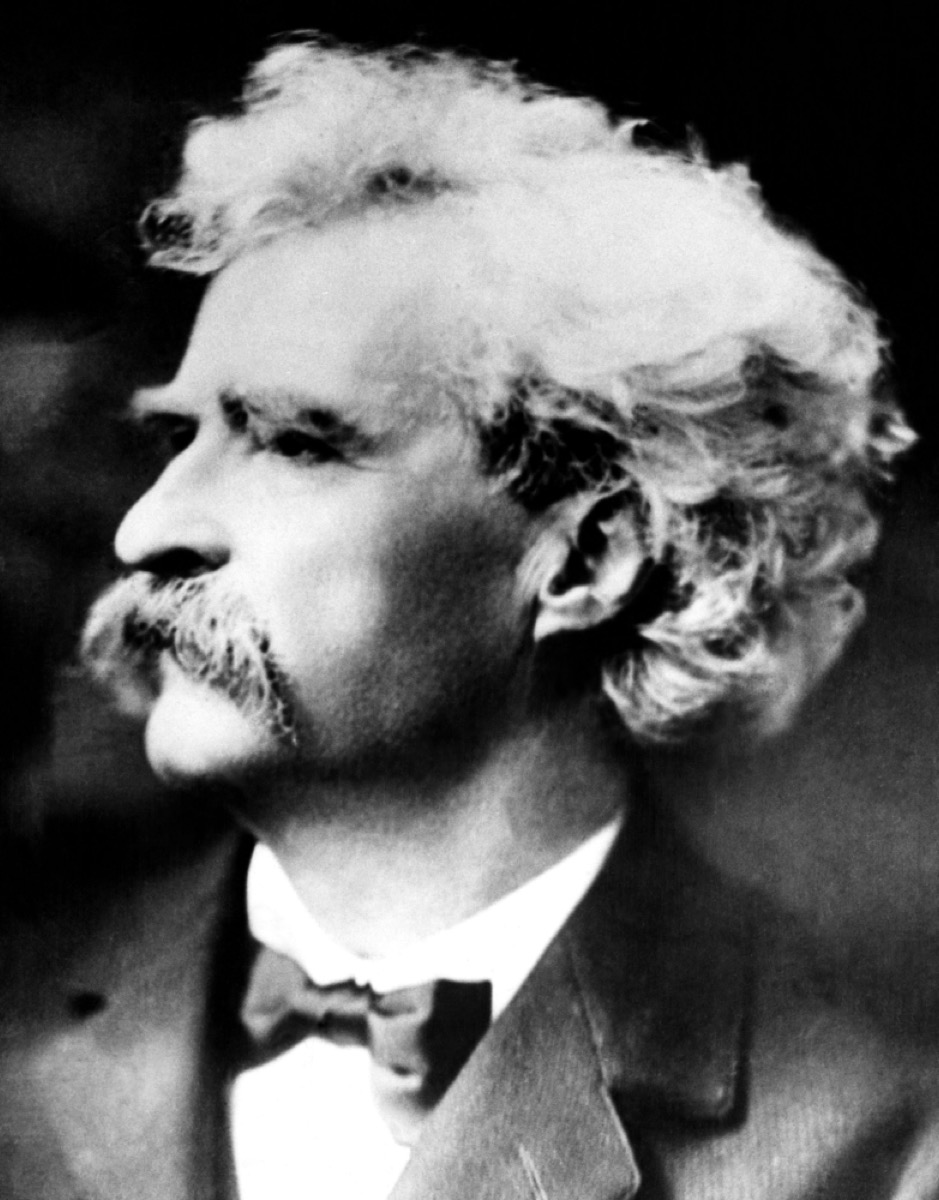

No, it wasn’t Al Gore who invented the internet. But the first person to dream about the possibilities of a globally connected community is just as surprising. Mark Twain imagined such a future in his 1898 short story “From the ‘London Times’ of 1904,” where he introduced readers to something called a “telelectroscope” that used the phone system to create a worldwide network for sharing information. This innovation, Twain wrote, would make “the daily doings of the globe… visible to everybody, and audibly discussable too, by witnesses separated by any number of leagues.” The next time you use Twitter and YouTube, always remember that the guy who wrote Adventures of Huckleberry Finn thought of it first.

The first atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945. The second one was dropped on Nagasaki a few days later. But the first “fictional” atom bomb was dropped in H.G. Wells’ 1914 novel The World Set Free. Though the book was published at least 30 years before the geniuses at the Manhattan Project began trying to create the ultimate weapon, Wells managed to capture the devastating effects of an atomic explosion. “Perished museums, cathedrals, palaces, libraries, galleries of masterpieces and a vast accumulation of human achievement whose charred remains lie buried,” he wrote, “a legacy of curious material that only future generations may hope to examine.”

Back in 1987, Omni magazine interviewed the popular movie critic Roger Ebert and asked him to predict the future of cinema. It was an ambitious request for a guy whose job involved rating films by putting his thumb up or down, but he took a stab at it. “We will have high-definition, wide-screen television sets and a push-button dialing system to order the movie you want at the time you want it,” he said. “You’ll not go to a video store but instead order a movie on demand and then pay for it. Videocassette tapes as we know them now will be obsolete both for showing prerecorded movies and for recording movies.” Two thumbs up for that prediction!

Alexander Graham Bell, better known to most people as the inventor of the telephone, made a surprising warning in a 1917 paper. The unchecked burning of fossil fuels would “have a sort of greenhouse effect,” he wrote, and it would eventually cause the Earth to become “a sort of hot-house.” What shall we do, he wondered, in a piece for National Geographic, when all the oil and coal dries up? His suggestions: Alcohol as an alternative fuel, and devices that would collect solar power from sunlight and use it as an energy source. His ideas didn’t get much traction at the time, but a hundred years later, global warming is the center of a worldwide debate.

When actor James Dean died in a car crash at the young age of 23, nobody saw it coming—nobody, that is, but his fellow thespian Alec Guinness. As the future Jedi Master (Guinness played Ben Kenobi in the Star Wars movies) explained in a BBC interview in 1977, he met Dean only once at a Hollywood restaurant. Dean showed off his new car to Guinness, bragging that it could reach speeds of 150 mph. “Some strange thing came over me,” Guinness recalled. “I said, ‘Please do not get into that car, because if you do … by 10 o’clock at night next Thursday, you’ll be dead.’” Guinness didn’t just predict the Rebel Without a Cause star’s death, but the exact date—September 30, 1955—it would happen.

Bill Gates didn’t become one of the richest people alive without bold and risky ideas. Back in 1999, he made a dozen predictions, all of which seemed preposterous at the time but some of which eventually came to pass. One forecast in particular seemed especially outrageous, even as we approached a new millennium. “Constant video feeds of your house will become common,” Gates wrote, “which inform you when somebody visits while you are not home.”

The Simpsons made a lot of eerily accurate predictions about the future—they jokingly claimed that Donald Trump would become president, for one thing—but every so often the show actually helped change the course of history. It happened in 1994, in an episode where Kearney asks his fellow bully to take a memo on his Newton, Apple’s early attempt at personal digital assistants. But when the bully writes down “Beat up Martin,” the device translates his handwriting as “Eat up Martha.” Almost two decades later, Nitin Ganatra, Apple’s former director of engineering for iOS applications, claimed that this mortifying moment inspired the new and improved iPhone software. “If you heard people talking and they used the words ‘Eat up Martha,’ it was basically a reference to the fact that we needed to nail the keyboard,” he said. “We needed to make sure the text input works on this thing. Otherwise, ‘Here comes the Eat up Marthas.’”

Most people in the late ’70s wouldn’t have recognized David Prowse’s face, but he helped create one of the most famous movie characters of all time. He was Darth Vader, the man behind the mask, and after Star Wars became a huge phenomenon, he was hounded by fans and reporters looking for clues not just about Vader but the future of the sci-fi franchise. During one appearance in Berkeley, California in 1978, he was asked about a possible sequel, and he spilled the beans in a big way, revealing that we’d learn in the new movie that Darth Vader was actually Luke Skywalker’s father. It was a bombshell, all right, and probably the world’s biggest spoiler. But there was just one problem: At the time he said it, an early draft of The Empire Strikes Back didn’t mention anything about Darth and Luke’s familial connection. That plot point didn’t come until much later.

John Elfreth Watkins was an engineer who was pretty sure he knew where the world was heading, and he shared his thoughts with Ladies Home Journal in 1900. Many of his predictions never came true—mosquitos and house flies haven’t gone extinct, and college educations aren’t free (unfortunately)—but he got some right with startling accuracy, like the advent of digital photography. “Photographs will reproduce all of nature’s colors,” he wrote. And they could be transmitted “from any distance. If there be a battle in China a hundred years hence, snapshots of its most striking events will be published in the newspapers an hour later.” Cameras around the world will be “connected electrically with screens at opposite ends of circuits, thousands of miles at a span.” The only thing he didn’t see coming was our tendency to use this amazing technology to take endless selfies.

How could a 19th-century Russian prince possibly have predicted the age of blogging? Well, not only did Vladimir Odoevsky imagine such a thing, the renowned philosopher, composer, and science fiction writer might have invented it, more than a hundred years before the internet even launched. In his 1835 novel titled Year 4338, he attempted to predict what the world would look like in 2,500 years, Odoevsky wrote that houses would be “connected by means of magnetic telegraphs that allow people who live far from each other to communicate.” Each house would publish a daily journal or newsletter, provide information “about the hosts’ good or bad health, family news, different thoughts and comments, small inventions, invitations to receptions,” and share it with the world. In other words, oversharing with strangers via technology. Yep, sounds like blogging!

When the Chicago Cubs finally won a World Series in 2016, after a 107 year drought, almost nobody saw it coming. Nobody, that is, except for a high school student living in California in the early ’90s. Mike Lee, a die-hard Cubs fan and student at Mission Viejo High School, was so confident that he knew when the Cubs would win that he included it under his senior photo in the school’s 1993 class yearbook. “Chicago Cubs. 2016,” he wrote. “World Champions. You heard it here first.” His pal Marcos Meza, a Dodgers fan, remembered the quote all these years later, and when the Cubs took it all in 2016, he shared the prediction with the world. “I thought it was so funny that I never forgot it,” Meza says.

An AT&T commercial from 1993 with Tom Selleck, the actor (and mustache) better known as Magnum P.I., predicted all the technological marvels we’d be enjoying in the coming millennium. Yes, it sounds like a joke, and some of it was—nobody is faxing from the beach, or tucking in their baby from a phone booth—but Selleck and AT&T got more than a few predictions right on the nose. “Have you ever crossed the country… without stopping for directions?” he asked. This was six years before President Bill Clinton declassified GPS technology so that it could be commercially available to everyday people, making it possible for drivers to get directions anywhere without an atlas. Today, driving anywhere without GPS offering turn-by-turn directions, sounds downright prehistoric. ae0fcc31ae342fd3a1346ebb1f342fcb There’s not much in Ray Bradbury’s 1953 dystopian novel Fahrenheit 541 that we wanted to come true someday, but there’s one detail that we’re glad became a reality. In the society of Bradbury’s book, they’re obsessed with entertainment and need to be constantly distracted by mass media. Many of them do so with “little Seashells” filling their ears with “an electronic ocean of sound, of music and talk and music and talk.” They sound just like today’s wireless earbuds, except with way more government mind control!

Few people saw the short film 1999 A.D. when it first came out in 1967, which is a shame, because it showcases a house of tomorrow that feels very much like the house of today. From push-button kitchens to “fingertip shopping” to “electronic correspondence machines,” it accurately predicted many modern conveniences that we take for granted in 2019. And for a deeper look at what that time was like, Here’s What It Was Like to Live Without Today’s Technologies We Totally Take for Granted.

Mark Twain was born just two weeks after Halley’s Comet appeared in the skies in 1835. As he remarked to his biographer, who published his book in 1909, “It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don’t go out with Halley’s comet.” It may’ve sounded like a joke, and it was likely intended as such. But true to his word, Twain died on April 21, 1910, just a single day after Halley’s comet returned.

Isaac Asimov, the legendary science fiction author and biochemistry professor, had a few thoughts in 1964 about what the world would look like 50 years in the future. Writing for The New York Times, he told readers that by 2014, “Gadgetry will continue to relieve mankind of tedious jobs.” People would be able to cook “automeals,” ready to eat within seconds, and complete lunches and dinners, “with the food semi-prepared … stored in the freezer until ready for processing.” There would also be devices capable of “heating water and converting it to coffee.” We may not have any robot butlers yet, but at least we have the microwaves, coffee machines, and Blue Apron that Asminov promised us a half-century ago!

The French general and military theorist Ferdinand Foch wasn’t all that impressed with the end of World War I. In fact, he seemed fairly certain that the so-called “War to End All Wars” was anything but. According to Winston Churchill, when Foch learned of the Peace Treaty of Versailles, he was deeply displeased that Germany would be left largely intact and remarked to Churchill, “This is not peace. It is an armistice for 20 years.” Turns out, he was pretty darn close: World War II officially began exactly 20 years and 68 days later. (Foch died on March 20, 1929, and therefore never saw his prediction come to pass.)

Most people remember science fiction writer Robert Heinlein as the author who predicted the Cold War and the nuclear arms race that dominated much of the late 20th century. Sure, that’s pretty impressive, but we’re way more impressed with how he inspired the waterbed. His 1961 novel Stranger In a Strange Land contained a convincing, detailed description of a mattress filled with water, which he called a “hydraulic bed”—though he never capitalized on actually bringing them to fruition. Just a decade later, in 1971, art student and inventor Charles Prior Hall secured a patent for the thing.

Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land is about alien creatures trying to fit in with human society, and within that narrative he creates a “typical” middle-class home of the future that isn’t that far off from what we have today, particularly when it came to personal computers. When a computer, or “stereovision tank,” was left unattended, Heinlein wrote, it became “disguised as an aquarium” filled with animated “guppies and tetras” swimming around. Or, as it’s more commonly described half-a-century later, a screensaver.

More than a hundred years before we learned that Mars has two moons, Phobos and Deimos, Jonathan Swift made an educated guess about the Red Planet. In his 1726 novel Gulliver’s Travels, he wrote about “two lesser stars, or satellites, which revolve about Mars.” Even more remarkably, he predicted their exact size and speeds of rotation. Given that no technology existed yet that would’ve made Mars visible, how could Swift possibly have known this? There’s been a lot of wild speculation, including theories that Swift himself might’ve been a Martian.

In Aldous Huxley’s groundbreaking 1931 novel, Brave New World, the London government of 2540 makes sure its citizens remain loyal by giving them “Soma,” a legal drug that “raised a quite impenetrable wall between the actual universe and their minds.” In other words, it made them content and unburdened by sadness or anger. “Eyes shone, cheeks were flushed, the inner light of universal benevolence broke out on every face in happy, friendly smiles.” If that sounds like modern antidepressants, you’re not the only one to notice. The Journal of American Physicians and Surgeons noted in 2016 that Huxley’s novel “set the stage for our love affair with mind-altering pharmaceuticals.”

Laugh In, Dan Rowan and Dick Martin’s hugely popular sketch comedy show, had its fair share of political commentary, but they always aimed for punch lines rather than accuracy. Still, they managed to do both in a segment called “News of the Future,” where they predicted not only the future presidency of Ronald Reagan—who at the time was the governor of California and not exactly an obvious candidate for the White House—but also the exact year of the fall of the Berlin Wall. This all happened in 1969, a full two decades before East and West Germany were reunited.

When he was just 11 years old, Colin Kaepernick was given a fourth grade assignment asking him to predict what he’d be doing with his life as a grown-up. If you expected Kaepernick to write “football player,” you’d be close. But no, the future NFL quarterback wasn’t about to be that vague. “I hope to go to a good college,” he wrote, “then go to the pros and play on the Niners or Packers even if they aren’t good in seven years.” The San Francisco 49ers, as you may recall, picked Kaepernick in the second round in the 2010 NFL draft. And for another look in the crystal ball, here are 25 Expert Predictions About the Future That Will Excite You. To discover more amazing secrets about living your best life, click here to follow us on Instagram!